Bernard Peter Hickey

son of

Patrick Hickey and Marcella Healy

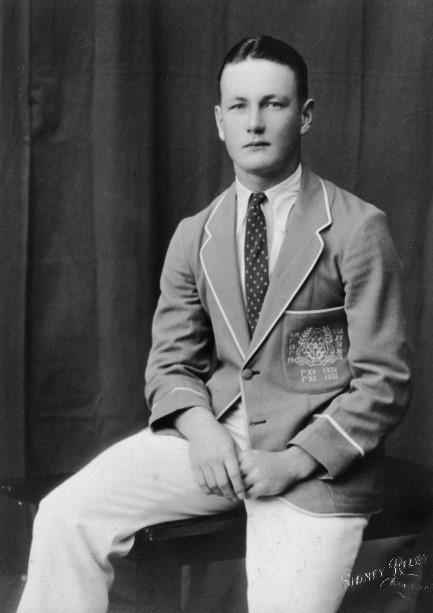

Bernard Peter Hickey, known as Peter, was born on 30 August 1913 in Toowoomba. Peter spent his early years in Cooyar, starting his schooling there on 2 September 1918, just after his fifth birthday. He was nine years old when the family relocated back to Toowoomba, where he was enrolled at St Mary’s Christian Brothers School.

Peter did well with his studies at St Mary’s,

passing the scholarship examination in 1928 and Junior Public Examination in

1930. He studied English, Latin, arithmetic, algebra, chemistry, and physics.[1]

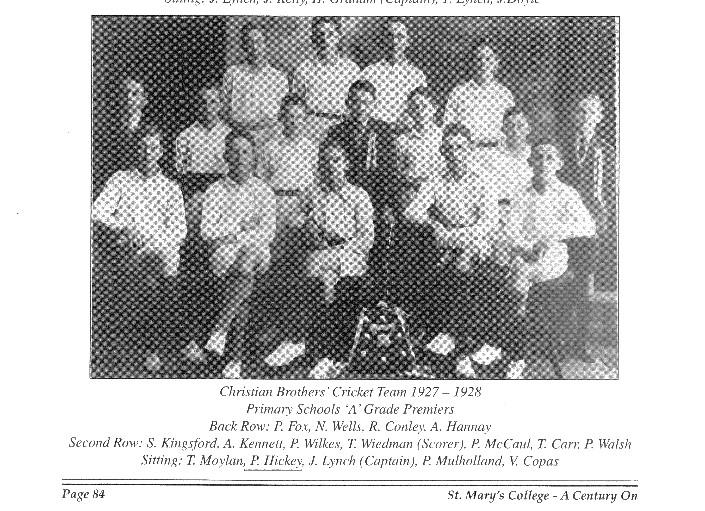

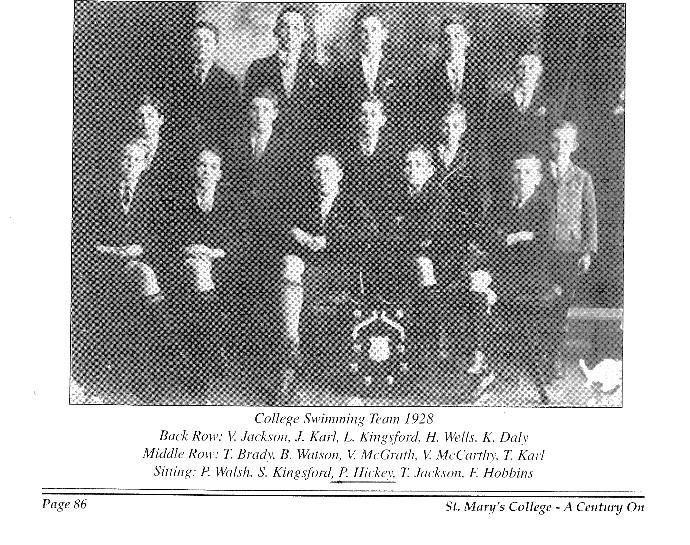

He excelled in the sporting side of school life, played rugby league and

cricket, and competed in swimming and athletics.[2]

[1] Toowoomba Chronicle and Darling Downs Gazette, Thursday 15 January 1931, p.12.

[2] Dwyer Kevin, St Mary’s College Toowoomba a Century On, 1999.

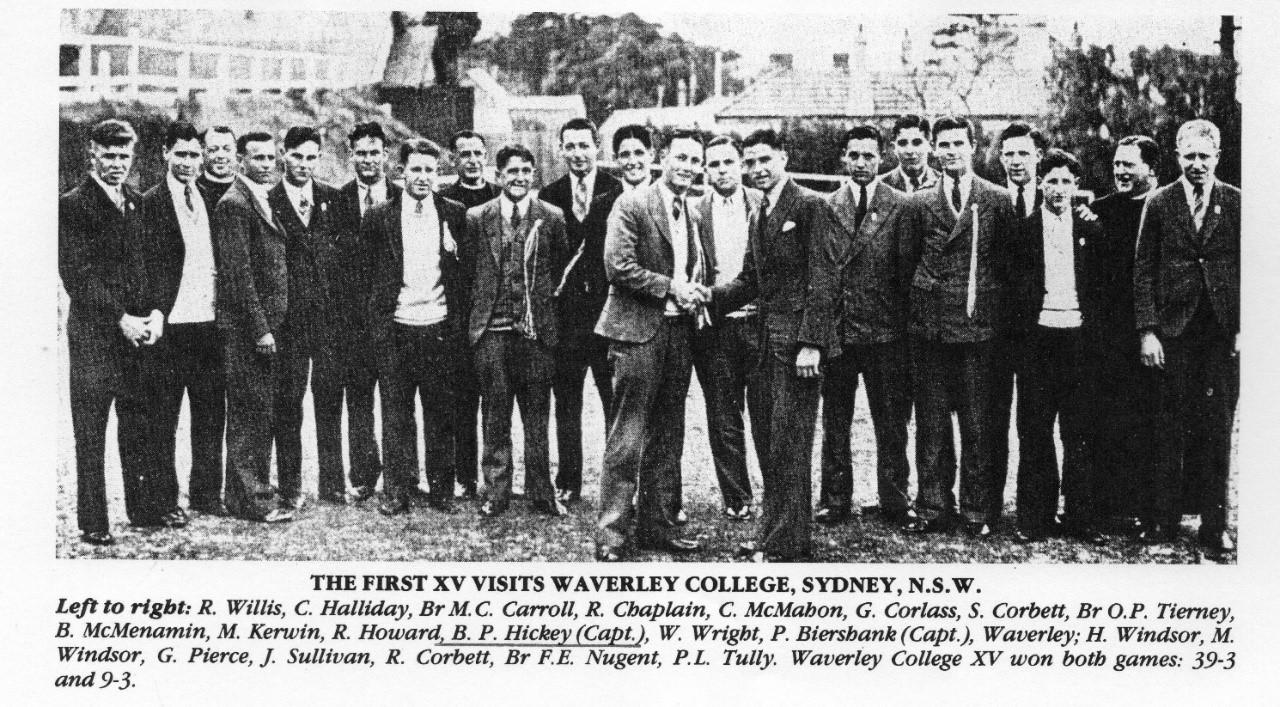

For the next two years, in 1931and 1932, Peter went as a boarder to another Christian Brothers school, Nudgee College, in Brisbane. Here again, he was prominent in the sporting activities of the school, as captain of the cricket and rugby union teams in 1932. The Nudgee first rugby team won the GPS premiership in both years that Peter played.

In 1932, the Nudgee rugby team travelled by train to Sydney to play against Waverley College, another Christian Brothers school. This would have been an exciting trip for the Queensland schoolboys. Unfortunately, they were beaten in the two games that they played.

Peter also won a gold medal for high jumping and came third in that event, at the Queensland junior athletics championships in 1931.

While at Nudgee College, Peter took part in debating and public speaking activities. He became quite accomplished in this area.

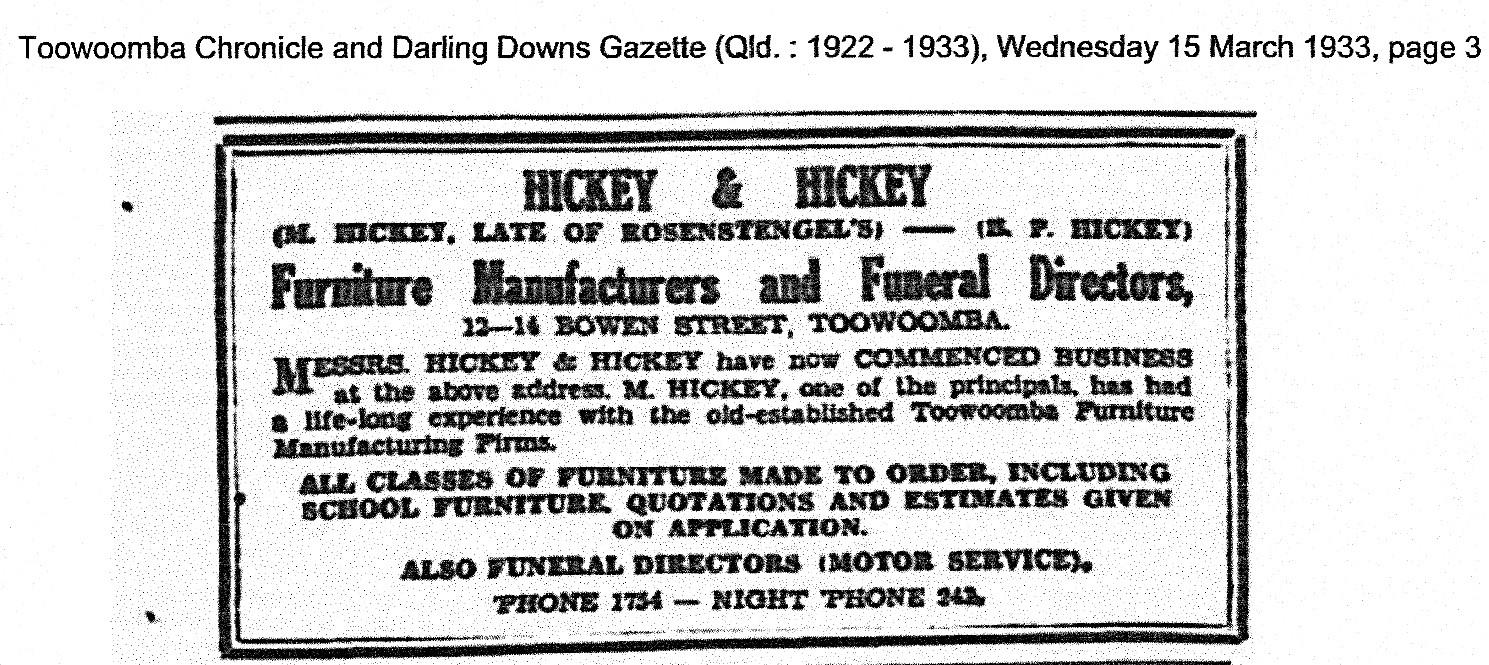

When Peter left school and returned to Toowoomba, he went to work with his uncle Michael Hickey, as a cabinet maker and funeral director. Michael had learnt his trade with Robert Dakers and worked later for Ed Rosenstengel, a very well-known furniture maker in Toowoomba, and later in Brisbane.

During the summer Peter played in the Past Brothers’ cricket team and also learnt to play golf.

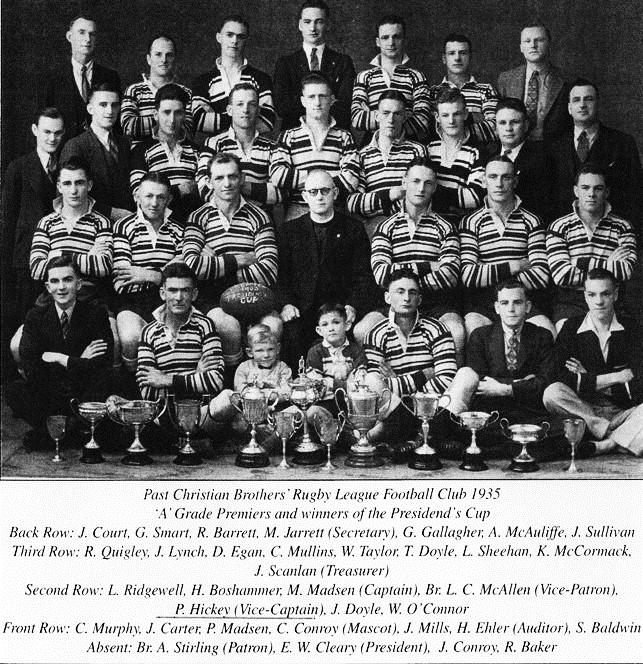

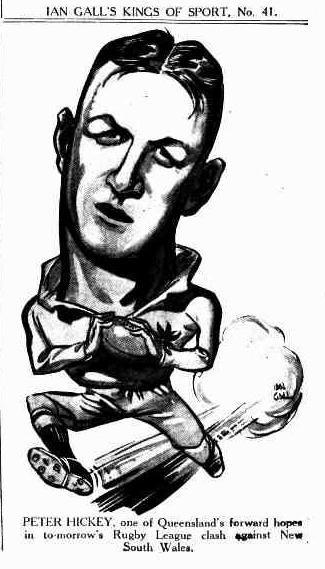

He returned to his rugby league roots and played in the forwards, with the Past Christian Brothers Club, for the next few years. He also played for Toowoomba, in the Bulimba Cup competition from 1933 to 1935. The Bulimba Cup teams were from Toowoomba, Ipswich and Brisbane. The competition began in 1925 and continued until 1972 when it was cancelled due to waning interest and greater emphasis on the Brisbane teams.

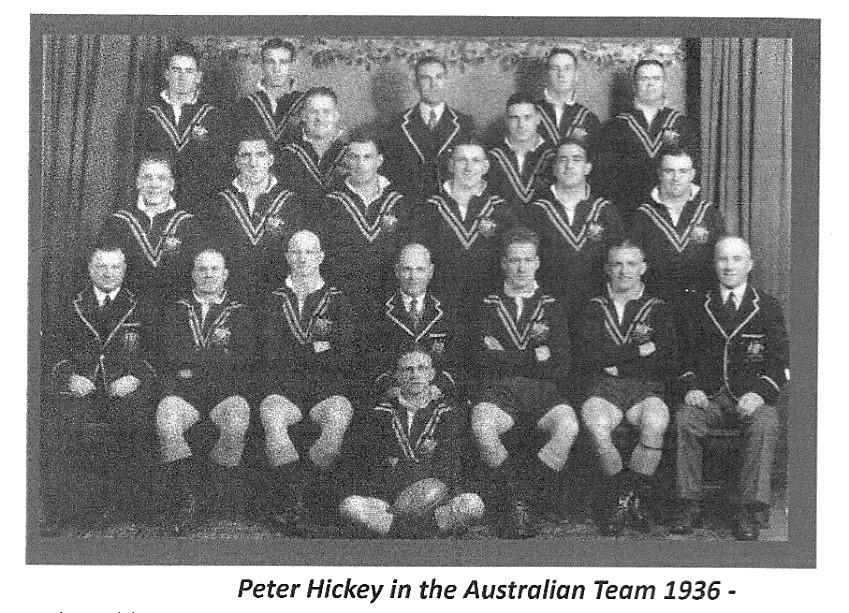

By 1936 Peter had moved to Brisbane, with his parents and brothers, at the York Hotel in Queen Street. He joined Past Brothers’ rugby league club and played with them for the next few seasons. At this time, he was chosen to play for the Queensland team in their games against New South Wales. Altogether he played eight games for Queensland against New South Wales in the 1935 - 1937 seasons

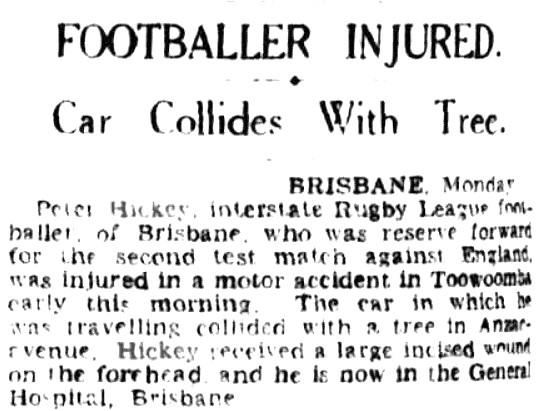

1936 was also a year when the English rugby league team toured Australia. Peter was selected as a reserve in the Australian team, to play on 4 July in the second test at the Gabba in Brisbane. It was a very wet day, which suited the English team. A large crowd of over 31 000 turned out to watch. Unfortunately, Peter did not get to play in the game which was won by the Englishmen 12 – 7.[1]

Courier-Mail, Brisbane, Qld. (1933 - 1954), Monday 26 April 1937, p.8

The Footballer of the Week — No. 4.

LION-HEARTED PETER HICKEY

As the dense crowd wended its way towards the exit gate at the Brisbane Cricket Ground on Saturday an enthusiast asked veteran, Ken McKay, who had been the best player on the ground. Came the reply: 'Peter of course!’ The fact that everyone within hearing knew who was referred to was a wonderful tribute to 23-year-old Brisbane second-row forward, Peter Hickey. His sustained brilliance and stamina stamped him as the most serviceable forward on the ground. On this display, he looks a certainty to be Les Heidke's partner in Queensland's scrummage against New South Wales at Brisbane and Sydney in June. If he further impresses in these struggles, he should have no difficulty in winning a place in the thirteen who probably will constitute the forward quota of the 28 players for the Kangaroos’ tour of England and France in July.

Hickey is an ideal type. He has the heart of a lion with his undoubted speed and great powers of anticipation. He is an immense force in deciding the issues of a conflict that is in the balance. Not quite so brilliant in the open as Collins can be, Hickey has developed into one of the most scintillating opportunists in the game. His cover defence is even greater than that of Collins. At times he appears to drop from the clouds to 'nail' his man just when it seems that an opposition score is a certainty.

Hickey received his earliest schooling in Rugby at Toowoomba Brothers and Nudgee College. He captained the latter and represented Combined Secondary Schools. However, his great League career really commenced when in 1934, at 20 years of age, he became a Queensland reserve forward. He quickly graduated from that class into a wearer of the maroon jersey, winning his representative spurs in 1935. Since then, he has never missed selection for a big

game. Hickey is the type likely to develop physically. At present he weighs 12 stone 2 lbs.

L. H. Kearney.

[1] Sunday Mail, 5 July 1936, p.13.

Early the next year, 1938, Peter announced that he would not be playing any football that season, because of a leg injury he received the previous year.[1] By May he must have changed his mind, as he applied to switch codes and again play rugby union for Brothers club, as he had played rugby union at Nudgee College. Objections were raised by the New South Wales rugby authorities. At that time rugby union was an amateur code, while in rugby league some payments were made to the players.

Truth Brisbane, Qld. (1900 - 1954), Sunday 15 May 1938, p.8

WILL Q.R.U. BAN LEAGUE STAR? HICKEY DID NOT PLAY YESTERDAY

White-Washing Now Vital Interstate Issue

THAT "SHAMATEUR" SYSTEM”

Although not officially notified of N.S.W. opposition to the reinstatement of the former Union and League player, Peter Hickey, members of the Queensland Rugby Union executive decided on Friday night that, to protect other players, Hickey should not play on Saturday. Queensland officials believe that protests from the South are inspired. They will review Hickey's case at the executive meeting on Tuesday night. "Truth" anticipates that, in view of the known facts, the Q.R.U. will decide to withdraw Hickey's registration, with a view to evading repercussions from N.S.W., and to avoid jeopardising the status of other players, who may subsequently secure State or international honours.

"Truth" interviewed Hickey yesterday and asked Peter did he receive payment from any Rugby League games and did the Q.R.U. know of it when reinstating him? He refused to say anything to either question, but admitted playing for Queensland in 1936 and '37, and stated that his injured knee, which had kept him out of any football this season, had stood a satisfactory test. An interview with Mr. Sunderland elicited the plain statements that Hickey, with others, had definitely received a £10 bonus for playing for Queensland prior to the Test of 1936, and £5 playing for Queensland against England. Harry says Hickey is only one of many who have received money from Rugby League and then gained admission to Union. The Hickey case appears to have put the sporting spotlight right on the white-washing of League stars to make them look almost lilywhite. Q.R.U. officials believe that their New South Wales confreres can't throw stones, either. However, it is believed that matters will be brought to a head. The Hickey case completes an indictment of the ‘shamateur’ system now operating, and unless New South Wales and Queensland dissolve partnership over this vital Union issue, it is certain that a basis of clear-cut amateurism0 must be established in both States, leading, subsequently, to the development of an Australian Board of Control. Meanwhile, it seems certain that Hickey will not play Rugby Union in Queensland.

Cairns Post (Qld.1909 - 1954), Thursday 9 June 1938, p.10

Hickey Rejected.

Advice has been received by the Queensland Rugby Union that the New South Wales Union will not agree to the acceptance of Peter Hickey to the Union ranks again. The chairman of the Queensland Union (Mr. J. H. Maguire) flew to Sydney during the week, but after a three-hour discussion, the judicial committee refused to endorse his acceptance.

As a result of this rejection Peter, still wanting to continue playing football in some form, applied to join Brisbane Valleys Leagues Club in 1939. This was Peter’s last football season in Brisbane before World War II started on 1 September 1939.

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. 1872 - 1947), Friday 10 May 1940, p.2

[1]Courier Mail, Thursday 3 February 1938, p.8.

THREE AIR FORCE RECRUITS WEIGH FORTY STONE

Allan Weller, Mick Murray and Peter Hickey at the R.A.A.F. Recruiting Centre in Brisbane

Three husky Australians, whose weights aggregate 40 stone, have enlisted in the Air Force. They are: Peter Hickey, a well-known footballer, Plainclothes Constable Mick Murray, and Allan Weller, of the Albert Hotel.

Murray is the heaviest of the trio, all of whom are solidly built. He weighs 14 stone odd. Peter Hickey turns the scales a few pounds short of 13 stone and Allan Weller is just over 13 stone. The three were at the R.A.A.F. recruiting office in Creek Street at 9 o'clock this morning awaiting their turns for medical examinations. They all passed.

All are very well known in Brisbane. Hickey is a State Rugby League player. He first represented Queensland in 1931 when his outstanding ability as a member of the Toowoomba Bulimba Cup team brought him before the notice of the State selectors. He then played in the State team each year until 1937. A great forward both in the rucks and in open play, he was a distinct asset to Brisbane football when he came to the metropolis. He also was keenly interested in cricket in those years, representing Toowoomba. In Brisbane, he played a season with the Valley reserve grade eleven.

Plainclothes Constable Murray joined the force four and a half years ago and was assigned to the wireless patrol car which post he held for two years. He then was transferred to the Criminal Investigation Branch and subsequently to Woolloongabba where he is at present stationed.

Weller was an enthusiastic Rugby Union player until a few years ago. Plainclothes Constable Murray conceived the idea of enlisting, he has a close friend already serving with the R.A.A F. and when he mentioned it to his two friends they immediately agreed to fall in line with the suggestion. His only regret, however, is that he is likely to be transferred to Ballarat (Victoria), for training as a wireless operator, and air gunner, while Hickey and Weller, who have enlisted as pilots, will have their elementary training in Brisbane.

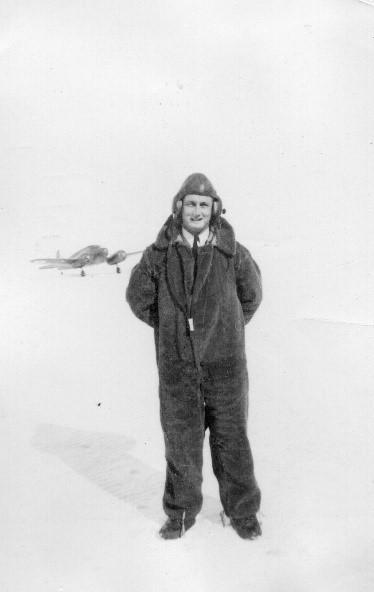

Peter Hickey signed his enlistment papers on 15 August 1940, at the age of 26 years 11 months. He was 5ft 10ins (178 cm) tall and weighed 168 lbs (76 kg). He did his first two months of training at Bradfield Park near Lindfield in Sydney, where he studied maths, armaments, anti-gas, morse code, law and administration. He passed all his exams at the end of the course. The passing-out dinner was held at the Wentworth Hotel in Sydney. Peter was selected by the men in his squad to give the principal speech of the evening.

Peter wrote regularly to his parents, and his letters, bound into a book by his brother Flem, are treasured by his family. The correspondence provides an insight into how the war affected just one of the combatants and his loved ones. There are many recurring themes in Peter’s letters – of separation, of love of family, of desperate desire for news from home. He writes also of the many kindnesses shown by the people in Australia, Canada and England. The letters are filled with good news and only rarely do the stress and horror of war arise. They are letters of a man protecting his family in more than one way, shielding them from the reality, that only one in three survived a tour of duty as a bomber pilot.[1]

His next move at the beginning of October was to

Narromine in New South Wales, where he began his flying training in tiger moth

and crane aircraft. He was issued with his flying kit of rubber overalls,

helmet, goggles, earphones and logbook. The hours were long, as the trainees

were in the air from 5.00to 8.00 am and

again from 9.00 am until midday. After lunch, there were lectures on armaments,

engines, rigging, signals, navigation, theory of flight and airmanship, then

flying practice again from 4.00 pm until 6.00 pm. On 3 November Peter

passed his first solo test. As he mentioned in a letter to his parents, ‘It is a great feeling to be up in the air on

your own, completely in charge of the plane.’

Peter passed all his flying tests at Narromine, which included cross country and blind flying by instruments alone. He was on leave from the twelfth to the twenty-eighth of December 1940, when he sailed to Canada for more flight training in the Empire Air Training Scheme. Peter was able to spend Christmas with his family and friends in Brisbane.

[1] Melissa Hickey Carroll, Signum Fidei, May 1995, p.12.

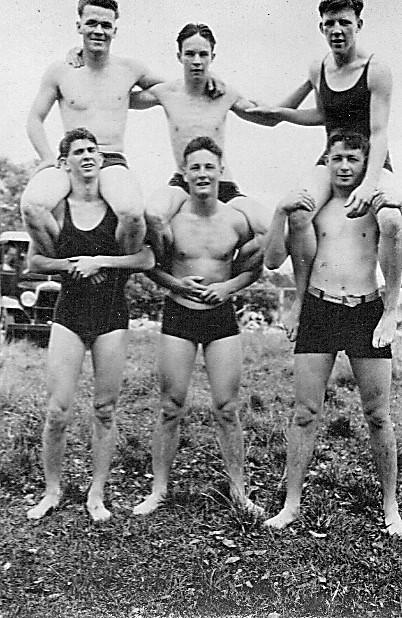

back row: Vince Hickey, Marcella Thompson, Bill Leahy, Doreen Nash, Les Nash, Ella Joyce

middle row: Eugene Hickey, Poppy Hickey, Patrick Hickey, Marcella Hickey, Molly Hickey, Flem Hickey

front row: Peter Hickey

Empire Air Training Scheme[1]

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the British government realised it did not have adequate resources to maintain the Royal Air Force in the impending air war in Europe. While British factories could rapidly increase their aircraft production, there was no guaranteed supply of trained aircrew. Pre-war plans had identified a need for 50 000 aircrew annually, but Britain could only supply 22 000.

To overcome this problem, the British government put forward a plan to its dominions, to jointly establish a pool of trained aircrew, who could then serve with the R.A.F. In Australia, the proposal was accepted by the War Cabinet and a contingent was sent to a conference in Ottawa, Canada, to discuss the proposal. After several weeks of negotiations, an agreement was signed on 17 December 1939, which would last for three years. The scheme was known in Australia as the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS).

Under Article XV of the agreement, it was proposed that each country’s aircrew would serve in distinct national squadrons, once they arrived in Britain. Eventually, there were seventeen Article XV R.A.A.F. squadrons, these being numbered 450–467 (but with no 465 formed). Four of these units were in Fighter Command, seven were in Bomber Command, and one was in Coastal Command. Another five were also formed in the Middle East. However, despite Article XV, the bulk of Australian aircrew served with RAF squadrons, not with a designated Australian squadron.

Some of Peter’s family went on the train with him to Sydney, when he departed for Canada. They were able to see the two hundred Australian airmen set sail for Auckland, the first port of call. Two hundred New Zealand airmen joined them there. The ship also made stops at Suva in Fiji and Honolulu, before arriving in cold Vancouver on 23 January 1941. From there the Australian and New Zealand trainees travelled by train over the snowy Rocky Mountains, to Saskatoon on the prairies. The temperature was -40°C on arrival. Their living quarters and classrooms were heated. Outside was another matter. According to one of Peter’s letters to his parents, ‘It is so cold that the hairs in your nose freeze when you are walking along.’

[1] www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/raaf/eats.

After months of flying training and study, Peter did his wings test on 2 May 1941 and performed well. He also received good marks in the ground subjects examinations. It was recommended that he be posted to a bomber squadron. The Wings Parade was held on 16 May 1941. Peter received a distinguished pass and his commission as a pilot officer.

It seems from his letters that Peter enjoyed his five months in Canada. The Canadians were very hospitable towards the airmen training in Saskatoon. New skills were learnt and friendships formed. Although the weather was very cold at the beginning of their stay, when the spring came and the snow melted, Peter was able to play some golf.

The new graduates travelled by train across Canada through Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Quebec and Montreal. In the latter city, Peter had three days’ leave. He visited the wireless air gunners school, where many Queenslanders were training and met up with quite a few men that he knew.

The last stop on the train journey was the port of Halifax in Nova Scotia, on the Atlantic coast. There Peter embarked on 8 June for England. The ship travelled in a slow convoy of supply ships and took twenty days to reach England. It was a relaxing time eating, sleeping, reading, playing bridge, watching movies and listening to records, before back to flying again.

After being moved about England for a few weeks, Peter’s first posting was to Moreton-In-The Marsh in the Cotswold area.

11 Jul 1941 I am quite settled down in England now and like it very much. We are at present stationed in a beautiful country village right in one of the prettiest parts of old England. The weather is glorious and the only thing that disturbs the serene quiet of the countryside is the roar of planes. We are doing a conversion course and are flying Wellingtons. We shall probably be doing night bombing.

Peter spent a few days in London, ordering uniforms from the tailoring firm of Austin Reid and visiting the sights with stops at the Savoy, Carlton and Regent Palace Hotels.

It was about this time that Peter’s mother Marcella, won a share in the first prize in the Golden Casket Lottery. She wired some of her winnings through to Peter, who assured her that he would not waste the money foolishly. He mentions later that he was thinking of buying a car, but that did not eventuate. He also heard about the births of two new nieces, Marcella, daughter of Eugene and Poppy, and Patricia, daughter of Flem and Molly. In his letters, Peter was always eager to hear about his nephews and nieces.

Peter wrote about his birthday on 30 August 1941 when he turned twenty-eight. This was to be his last birthday.

I received your cable wishing me many Happy Returns on Friday 29th and was glad to hear you all are well at home. I had a really lovely birthday, as enjoyable as it was unexpected. We finished work on the station about two o’clock on the afternoon of the 30thand as we were well up in our work, we were free until Sunday night. We were at a loose end and did not know what to do with ourselves when we received an invitation to Batsford Manor, the home of Lord and Lady Dulverton (Gilbert Wills, a tobacco millionaire). It is only about three miles from our quarters and we arrived there at about three o’clock, two Canadians, another Australian and myself. They have a beautiful home amidst glorious surroundings and acres of parklands and gardens. We played tennis in the afternoon or should I say attempted to play, as my tennis is pretty lousy.

We then had afternoon tea in a huge old English dining hall, replete with men-servants and the dignified old butler. After tea the rest of the boys went for a walk through the gardens and park with Lady Dulverton while I played ping-pong and romped with the children, nieces of hers, holidaying there. It was a rare day of bright sunshine delightfully cool and one of the few days on which it has not rained at some time or another.

We wished to leave about seven o’clock, but the lady of the house would not hear of it and insisted on us staying for dinner and all going to a cinema at Chipping Norton later. Well, we stayed and saw a very fine film ‘Spring Meeting’ and also ‘March of Time’ all about Australia and their war effort, this was quite interesting for us. We were driven to camp by a retired Colonel of the army about midnight after a wonderful day at the home of a most charming and gracious English family.

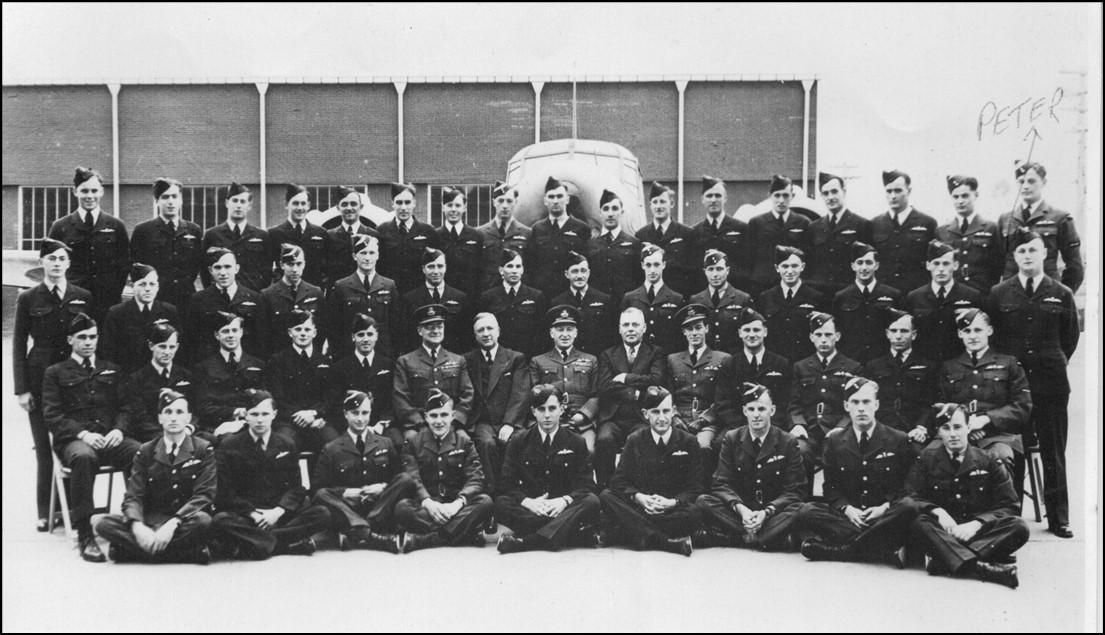

Soon after Peter was sent to the newly formed 458 Squadron, based at Holme-on-Spalding-Moor in the East Riding of Yorkshire, 32 km south-east of York city. In the 1940s the village was rather isolated and surrounded by farmlands.

458 Squadron R.A.A.F

No. 458 Squadron was a Royal Australian Air Force squadron that operated during World War II. It was formed in Australia under Article XV of the Empire Air Training Scheme. The squadron flew various versions of Vickers Wellington bombers, first in Europe and later in the Middle East. It was disbanded in mid-1945, following the conclusion of hostilities in Europe.

In Europe

No. 458 Squadron was formed at Williamtown, New South Wales, on 8 July 1941 as an Article XV squadron under the terms of the Empire Air Training Scheme. Consisting of only ground staff, the squadron departed for the United Kingdom in August to join other personnel assembled at R.A.F. Holme-on-Spalding Moor, where the squadron was officially established as No. 458 (Bomber) Squadron on 25 August 1941. From the outset, the squadron drew personnel from many different countries, with many coming from Britain, Canada and New Zealand, as well as Australia.

Equipped with Wellington Mk.IV bombers, No. 458 Squadron formed part of No. 1 Group R.A.F. of Bomber Command. It participated in its first operational sortie on 20/21 October, when ten of its aircraft joined in night attacks made against the ports of Emden, Antwerp and Rotterdam. Further attacks were made against industrial targets in France and Germany over the course of several months as part of a strategic bombing campaign. In addition, the Wellingtons were involved in mine-laying operations along enemy-occupied coasts. In late 1941, No. 458 Squadron provided a flight to help raise the newly formed No. 460 Squadron R.A.A.F. At the end of January 1942, the squadron was withdrawn from Bomber Command to serve in the Middle East. Losses during the war amounted to 141 personnel from 458 Squadron being killed, of whom 65 were Australian.[1]

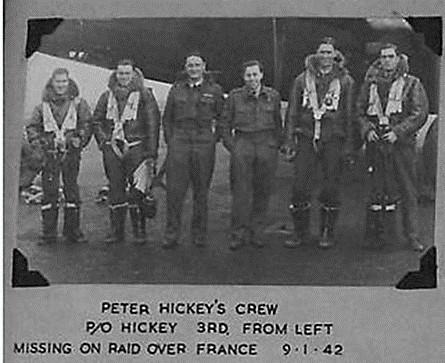

The crew of Peter’s wellington bomber R1785 was an international one. Besides Peter as a pilot, there were two other Australians, Victor W Johnston (co-pilot) and William W Forgan (machine gunner). Robert Burnie (bombardier) from Auckland New Zealand, and two Englishmen Fred Hinton from Leicestershire (rear machine gunner) and Albert S Austin from Birmingham (radio operator), were the other members of the crew.

L to R. Fred Hinton, Robert Burnie, Peter Hickey, Albert Austin, Victor Johnstone, William Forgan

[1] No. 458 Squadron RAAF - Wikipedia.

Peter took part in the first operational raid by 458 Squadron to Emden, northeast of Amsterdam, on 20 October. He commented in his letter, ‘The flack flying around looks quite pretty as long as it does not get too close.’ On 22 October, coming back from a raid at Brest, on the coast of Brittany in France, the aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire. The starboard engine had failed and the port petrol tank had been holed and was empty.[1] Peter described the experience in his letter to his parents to reassure them of his safety.

I

have had some amazing experiences since I last wrote to you, and have been very

lucky. We were coming back from a raid over the continent the other night.

After we had crossed the English coast, an engine packed up on us and the

aircraft started to act alarmingly. We did everything in our power to keep it

in the air, but it was impossible. Finally, we had to bail out.

[1] https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=1054991pp. 37 & 38

We were very near the ground and were only at about 1000 ft (304 m) when I jumped. I was very lucky and got away without a scratch. Of the crew of six, one chap (Sgt. R J Hobbs) was killed and we cannot understand what happened to him. He should have been the first to get away being the rear gunner. The other chaps are quite o.k. with a few slight injuries. I can only thank your prayers for my deliverance. We were also fortunate to get across the sea before the trouble started as we must have been hit by flack over the target.

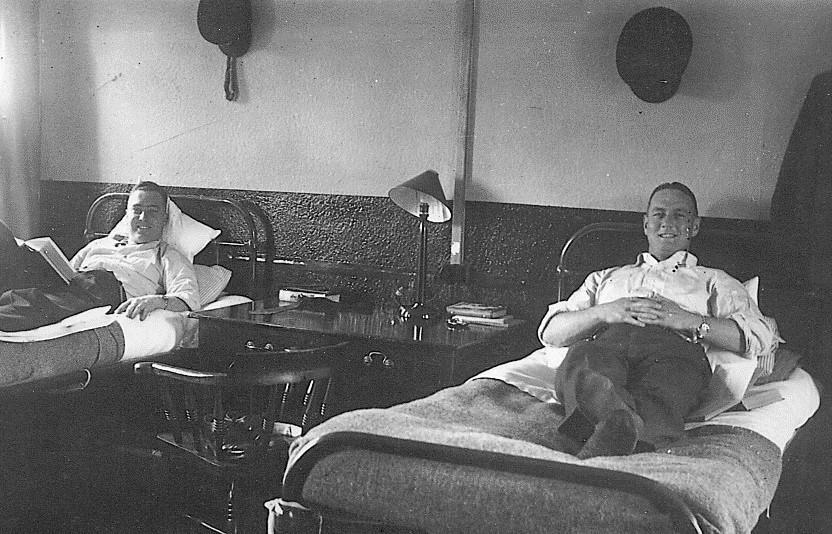

The crew were given four days’ leave after this incident and Peter and Bob Burnie went to London. During another leave a few weeks later, Peter met up with his friend Allan Weller, they were astonished to see each other, as this article in the Australian Women’s Weekly relates.

The Australian Women’s Weekly(1933 – 1982), Saturday 24 January 1942, p.8

R.A.A.F. pilots’ London Reunion

By Beam Wireless from Mary St. Clair, Our Special Representative in England

Two Brisbane boys, Sergeant-Pilot Allan John Weller and Pilot Officer Peter Hickey, met accidentally in London the other day while both were on leave and discovered each had mourned the other as lost. Allan and Peter went to school together, joined the R.A.A.F together, went to Canada together, won their wings together and came to England together. Allan was posted to an R.A.F bomber squadron, Peter joined the first Australian heavy bomber squadron.

Peter had parachuted from his shot-up machine above Salisbury Plain and landed unscathed though reported lost through Air Force unofficial ‘grapevine’, whereby word spread from squadron to squadron.

Allan had landed in the North Sea and was reported lost the same way, though actually picked up by a destroyer. The dramatic reunion occurred some weeks later.

“Peter, you old so-and-so, I thought you’d gone weeks ago,” said Allan.

“I was just going to write to your mother, Allan,” said Peter “It is good to see you again.”

Both of Irish extraction, they humorously dramatized their adventures to each other. “I left my money, clothes, and chocolate cake I had given me for Christmas with my friends,” said Allan. “Shows you the kind of pals they were, they’d spent the money, eaten the cake, and worn the seat out of my best pants before I’d been missing a few hours.”

“I thought with my head bandaged up I’d be a little hero: and that blonde girl in the W.A.A.F. might fall for me. But not a bit of it.”

“The C.O. rushing past, thrust out an arm to pat my shoulder, halting his steps just long enough to say, ‘Good show, old chap, glad you’re back. Have a few days leave to forget all about it.’

Peter said: “Well, I was so delighted I was unhurt that I hurried back to the squadron thinking that they could not do without me. But my enthusiasm was soon dampened down. The C.O. said: ‘You’ll have a bit of reaction, take a few days leave’.”

Both boys are now captains of Wellington aircraft.

Allan said: “We were singing a song as we came down. It ran: ‘Out of petrol, out of petrol, out of petrol just now. Where’ll we land, where’ll we land, where’ll we land just now. In the North Sea, in the North Sea, in the North Sea just now.”

“Then the navigator, who is a Sydney bloke, Bill Maher, sang ‘Get a bearing, get a bearing, get a bearing just now,’ and the wireless bloke would give the next verse: ‘Set’s not working, set’s not working, set’s not working right now.”

“It was a raging sea we landed on. We sang in that boat, told our life histories, ragged the rear-gunner, who wouldn’t send up a prayer because he said he was an agnostic.”

“Between bailing, singing, hoping and praying for the navy to show up in the darkness, we worked to convert the rear-gunner. Finally, just as the destroyer showed up, young Tailend Charlie admitted he was going to church the very next Sunday.”

Peter was killed two weeks before this article was published in the Australian Women’s Weekly. His friend Allan Weller, was killed when his aircraft was shot down in Germany, not long afterwards, on 28 March 1942.

Operations for 458 Squadron continued until the New Year, but the weather in northern Europe played a dominant part. Rain, fog, ice and snow intervened. During November 1941, though crews went on training flights over England, only on two occasions, the seventh and fifteenth November did the climate allow night raids from Holme-on-Spalding-Moor. Peter took part in both of these raids. His Brisbane friend Ron Furey, piloting another Wellington aircraft of 458 Squadron, was killed in the second raid.[1]

In a letter about this time, Peter mentions being asked to play football with the Leeds rugby league club. He replied that it would interfere with his work, and the Air Ministry frowned on officers playing a professional type of football. Later, he mentions playing a game for the R.A.F. against Cardiff.

In December 458 Squadron flew four raids to Calais and Boulogne in France, Ostend in Belgium, and Aachen, Dusseldorf and Cologne in Germany. There were no fatalities from these raids.

[1] Peter Alexander, We Find and Destroy, The 458 Squadron Council, 1979.

Peter’s last letter to his family was written on Christmas Day 1941.

Dearest Mum and Dad,

Well, here I am on Christmas Day in England. Although I am 12 000 miles away my heart is at the York in Brisbane today. I am going through the whole day at home in my mind. Midnight Mass with Vince, Les Nash and the boys after a busy night. Then home to bed for a good sleep-in on Christmas Morn. Then to be wakened up by the kiddies coming in with the toys Father Christmas has brought along. Peter, Pat, Marie, Marcella and the babies. Then we are up and into the car for our usual Christmas Day visits to all the folks we know. A spot here, a singsong somewhere else, dashing off in the cars, trying to fit them all in and not be late for Christmas Dinner. Home, and the house full up with brothers and sisters and boarders and all the children, all in happy festive spirit. A spot at the bar, I can even hear Jeanie Cocks laughing and see young Tiger Thompson racing around the counter.

Then to dinner and the popping of corks and bon-bons. The happy speeches with Pop at his best and the champagne flowing freely. Then giving the staff lunch and everybody striving desperately to get Miss McErlane a wee bit ‘foo the noo.’

After dinner away for a drive with the children and back home for a singsong later. Ah, happy memories which we shall and will live again.

We all get a little home-sick and a wee bit sad on these occasions but still, we make the best of it and do really have a happy time here. We are a very happy family. Most of us are Australians and we are all certainly wonderful friends. They are a grand lot of chaps here and it is amazing how we love to get back to our Squadron whenever we are away on leave.

We are most of us the original members of 458 Squadron and we are getting a good name and we are proud of our achievements so far. Yet we are only fledglings but fast growing in experience and striving to make our Squadron the best in England.

The Squadron put up a fine performance over Germany the other night. Our Squadron Leader had bombed his target and was returning when he noticed far below the moonlight shining on an enemy plane. Cutting the motors, they dived quietly down after him. The enemy, all unsuspecting, was coming in to land. When he was 50ft from the ground, Tommy, the front gunner in our Squadron Leader’s plane opened fire and shot them into the deck. Then away they raced at 100ft over the ground in their big bomber, shot up a gasworks, then a train and home they came to base. It was a great effort.

We are gradually getting our Mess very comfortable. We have a billiard table now, also ping-pong, darts and our squash court is working. Squash is a great game but I have not played much of it yet.

I had a letter from Allan Weller the other day. He is doing very well and is quite happy. He had lost a bit of weight when I last saw him and was looking real well.

I have had a lot of mail from you all at home lately, it all seems to come at once. Letters from you, Mum, two from Vince and two from Flem also from Eugene, Doreen, Marcella, also from Frank Bennett and Owen Weller. It was really great hearing from you all and Vince’s letters are just packed with news about the York and all the people there. I get some great laughs out of them. I do hope you are getting mine although now with the war in the Pacific, mail is going to get harder and harder to go through.

I have been really worried about Australia and you all. Those nasty little brown pests are doing a lot of harm. Please God they will never get down to Australia. How we would all love to be sent out to fight against them and teach the little devils to stay in their own back yard. There is going to be a mighty reckoning. Day by day our strength is increasing on land, sea and air. Day by day we are hitting harder and harder. This year is going to make an immense difference and I sincerely think and hope that this time next year the war will be won and we all be dealing out a terrible and lasting punishment to the inhuman monsters to whom nothing decent and good and clean is sacred.

I received some canteen orders from the L.V.A. (Licenced Victuallers Association) the other day which should come in handy. I still get some very fine letters from Canada and also received some Christmas presents from Mrs Guthrie and her daughter, Elsie, in Canada: a tie, handkerchiefs, cigarettes, chocolate, cheese and biscuits. They have been wonderfully good to me.

Rupe Holmes from Brisbane is doing very well here too. Rupe is captain of his own crew and is a really good pilot and a fine chap. He is one of my best mates, one of the best hearted chaps in the world, always happy and impossible to get out of sorts. The other night our Wing Commander, Tommy Howlett, the Sgt gunner who shot down the Messerschmidt, and Rupert Holmes had an argument about running. ‘All right,’ says the Winco, ‘half past nine in the morning at the aerodrome, £1 each and the winner takes it.’ The stakes were put up and the whole Squadron was out to watch and side bets galore. The old Rupe Holmes just romped home and collected the money.

Well Mum and Dad, please remember me to all in Brisbane. Keep up the prayers and please God I shall be with you all again in the not too distant future.

Your loving son

Peter. xxxx

In January 1942, the weather in England was bitterly cold. As it happened, it was the last month of operations for 458 Squadron at Holme-on-Spalding-Moor, with Bomber Command and in England. In February, the Squadron was relocated to the Middle East. The night of 6 January was the first night of 1942 for a raid by 458 Squadron. The German battleships,Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, at Brest harbour, were the targets but they were not damaged. Four crews were sent out again the next night but again did not achieve their objective.

Again, on 8 January four crews from 458, but not Peter’s, were sent to Brest with the crews and the defending anti-aircraft gunners playing a rather dangerous game of Blind Man’s Bluff. Low cloud cover obscured the targets. All planes returned to base.

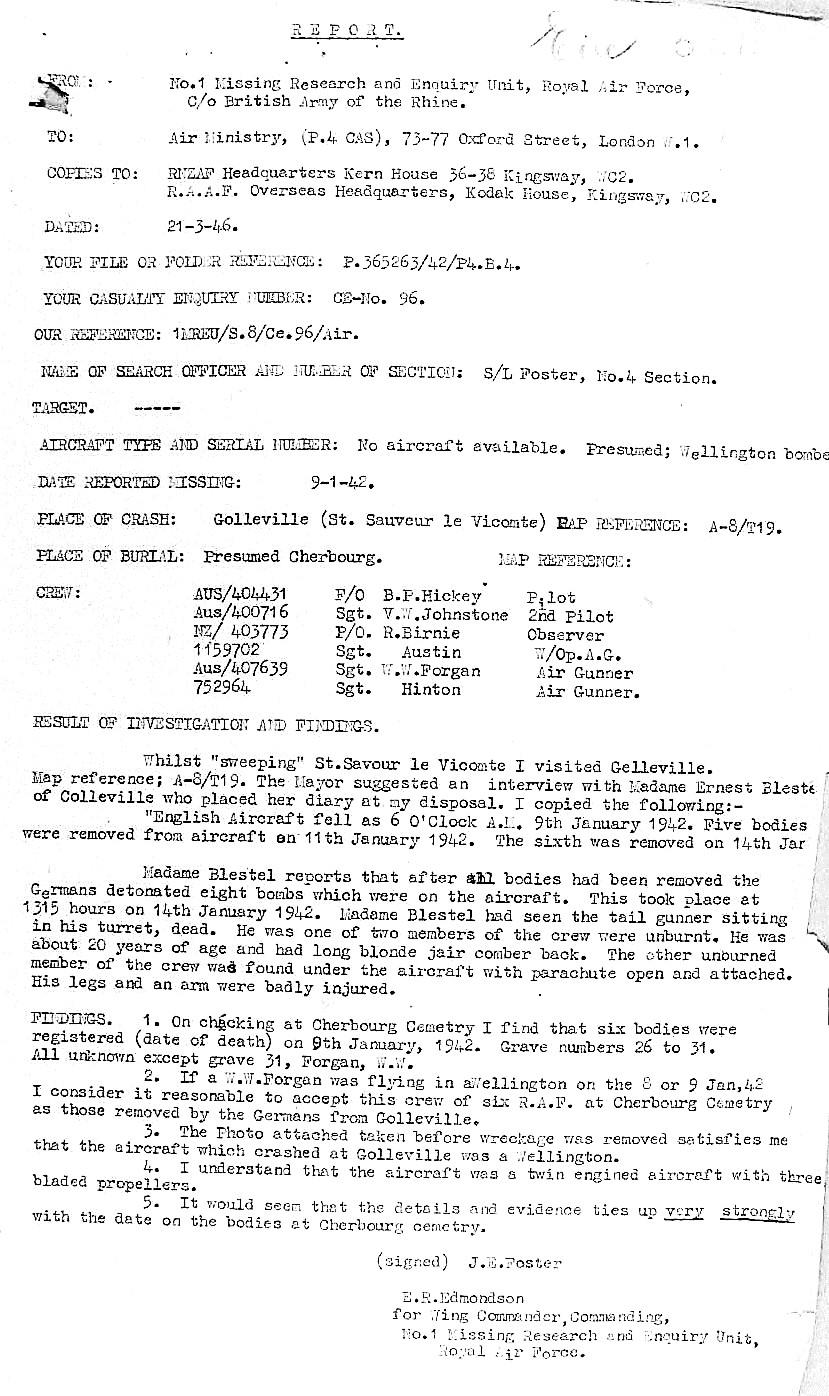

In the early hours of 9 January, thirty-one aircraft from various Squadrons were sent to Cherbourg on the coast of Normandy in France, as a diversion to the even greater number of planes sent again to try to sink the two German ships in Brest harbour. Among the Wellington bombers, were three from 458 Squadron piloted by Peter Hickey, Rupert Holmes and Bert ‘Judy’ Garland. Of the three only Holmes returned safely. Garland’s aircraft was disabled by anti-aircraft fire. Over Dorset, on the way back to base, the aircraft went into a steep dive, hit some high-tension cables and burst into flames. Only the pilot and co-pilot survived and the rest of the crew were killed.

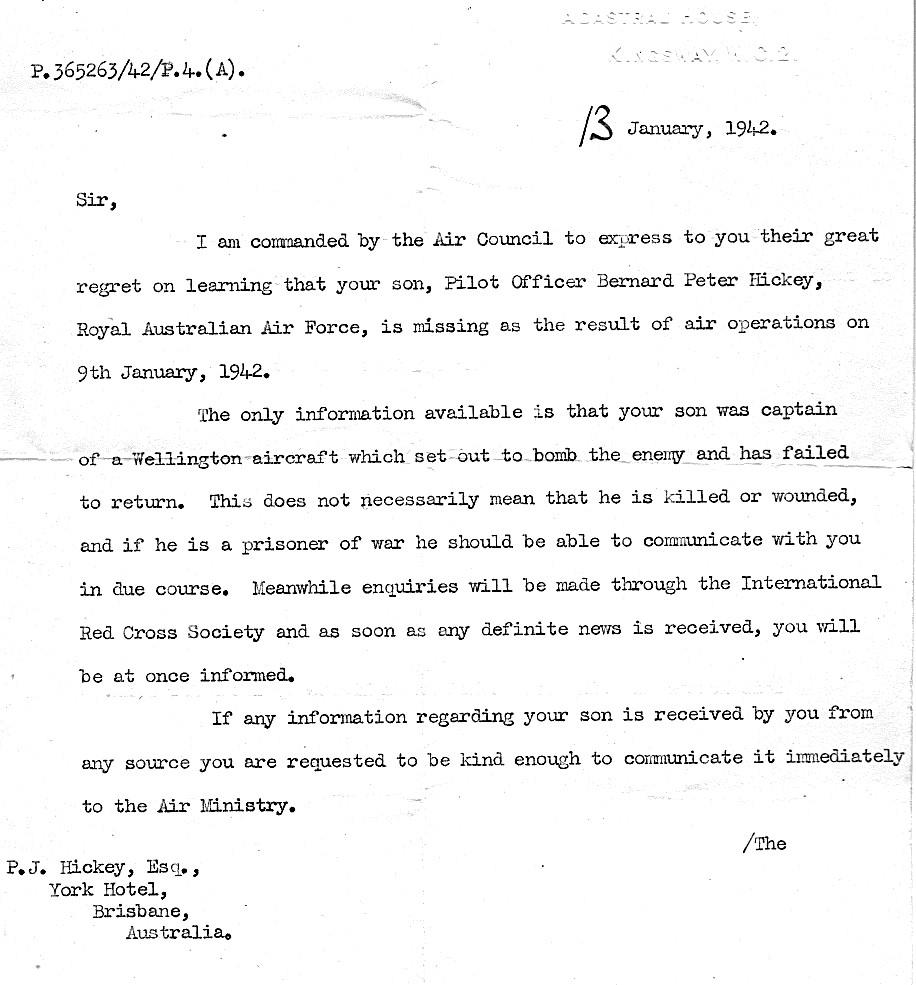

Peter’s Wellington R1785 took off at 4.35 am, the weather conditions over Cherbourg were appalling, snow was falling and visibility was just about nil. Only three of all the attacking aircraft were able to drop their bombs and many turned back. Peter’s plane did not return to the Squadron’s base at Holme-on-Spalding-Moor. Wellington R1785 had disappeared completely from view. The crew was first posted as ‘missing in action’ and later as ‘presumed dead’ and Peter’s father was informed of the disappearance of the aircraft.

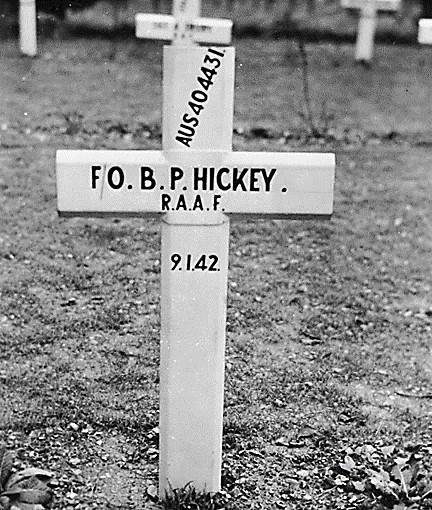

It was not until April 1945, that the Air Ministry received details of the fate of Peter Hickey and his crew of R1785 when the Missing Research and Enquiry Unit visited the cemetery at Cherbourg. By this time, Peter’s father Patrick had died. Six graves were identified though only one, that of William Forgan had a name. Later the other names were added to the crosses on the graves.

Another letter giving more information about the crash was received by the Air Ministry in March 1946 but it is not known if this was passed on to Peter’s family.

Extract from Article on the 458 Squadron Website Newsletter 235 August 2009[1]

Rob Forgan, nephew of William Wallace Forgan

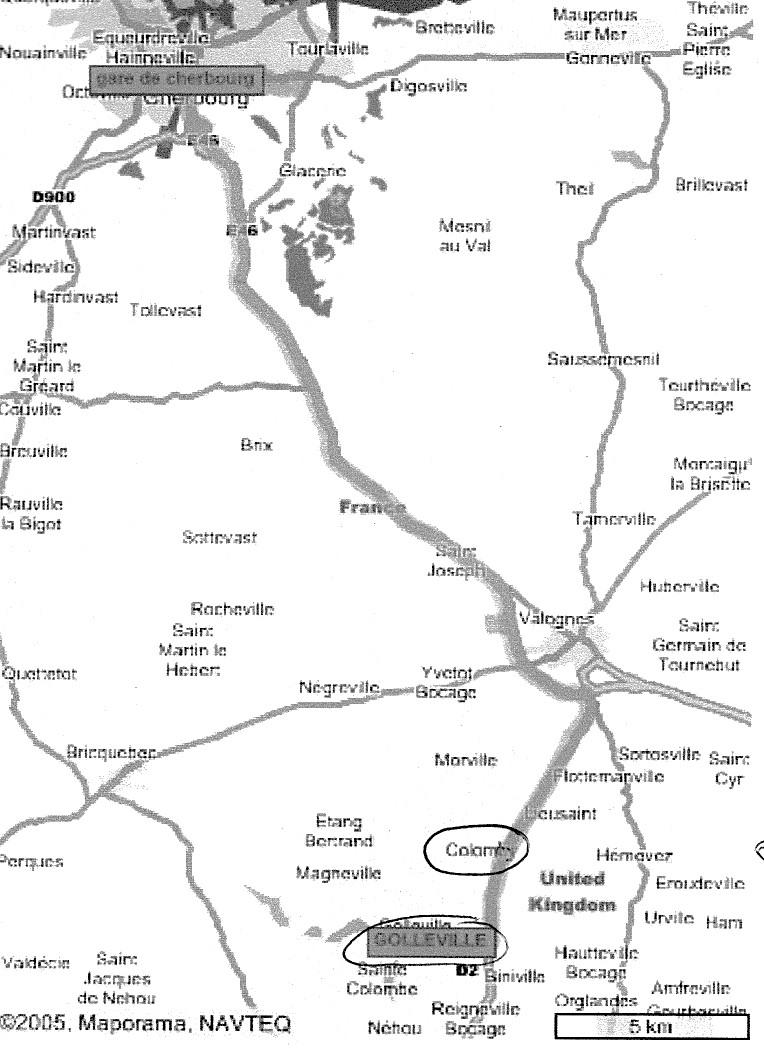

The fate of R1785 and the crew remained a mystery to relatives for over sixty-six years until Georges Dennebouy, an Air France captain, began researching a wartime incident on his family’s farm at Colomby in Normandy. In time, Georges teamed up with three other researchers, Mickael Simon, Claire and Claude Letellier, who had started to unravel the mystery a decade earlier by interviewing and recording the accounts of eyewitnesses of hundreds of pre-D-Day aircraft crashes over Cotentin in the department of La Manche, in Normandy.

It was in the winter of 1942 that Georges’ grandmother, along with other locals, saw a plane in flames flying at low altitude before it crashed into a snow-covered orchard before dawn. Together with other inhabitants they were on the scene before the Germans, but were powerless to do anything as the aircraft was on fire, except for the tail section and were not helped when German soldiers roughly made them leave the scene.

Two days later the Germans requisitioned two local farmers, a teenager, Joseph Anquetil and Mr August Mulot, a veteran of the Great War, to recover the bodies, and place them in coffins provided by the occupying forces. The bodies were awfully calcinated except for the young blond-haired tail gunner who remained trapped in his turret, the floor was strewn with wrappers, a testament to the loneliness of a rear gunner’s station. Joseph Anquetil remembered very well the military honours given to the victims by the German soldiers who presented arms and who filmed the scene.

A few days later, a group of Germans began to salvage parts of the plane, but to their horror, they discovered that the plane still carried its eight bombs of 250 lbs! Bomb disposal experts were called in to detonate the bombs and the enormous explosion volatized the Wellington with one of its engines leaping well over one hundred metres.

The Germans then made a macabre discovery when they found a sixth body under the wing and ordered another inhabitant, a youthful Roger Blestel, to remove the seriously mutilated body and place it in a coffin. This proved to be the body of Wally Forgan, the front gunner, who is presumed to have attempted a parachute jump, as he was hung on the wing at the end of his suspending rods that somehow snagged the wings as the plane made its fiery descent.

In 2005, the group of amateur historians undertook a ground search of the Breul farm crash site to confirm that the wreck was indeed a Wellington, and to match the crash to the graves of six allied airmen buried in the old Cherbourg cemetery.

Among the pieces of recovered twisted metal in the soil at the crash site, there was a silver signet ring engraved LMM. This did not match any of the names on the graves. It was not until later that Mickael Simon reversed the ring, and saw it read WWF, the initials of William Wallace Forgan.

In March 2006, Georges Dennebouy and his wife Liliane, flew to Australia to meet with relatives of the Hickey and Johnstone families and to return the ring to the Forgan family. The wonderful work of Georges, Mickael, Claire and Claude gave closure to families in Australia, New Zealand and England.

[1] www.458raafsquadron.org/education/lestwe forget.

The silver ring engraved WWF belonging to William Wallace Forgan found at the crash site.

October 2008 at Golleville memorial ceremony

Peter Hickey’s story does not end there. On a sunny Saturday afternoon in early October 2008 members of the crew’s families from Australia and England gathered with many of the inhabitants of Golleville and surrounding villages. Also present were members of the French National Assembly, Squadron Leader Tranter R.A.F., mayors past and present and other dignitaries. They gathered to unveil a magnificent grey granite memorial stone in the shape of the tail of the plane, engraved with the names of the six crew members of R1785. Christopher Hickey, a grandnephew of Peter and great-grandson of Patrick, represented the Hickey family. Christopher’s parents, Barry and Jean, also visited the memorial with Georges Dennebouy in 2009.

As Georges Dennebouy remarked at the dedication ceremony

This memorial will serve to remind the following generations of the enormous sacrifices made by those who came to our aid so far from their own homes, family and country.